Traditional Female Moral Exemplars in India

Traditional Female Moral Exemplars in India

by Madhu Kishwar

© 2001 by the Association for Asian Studies, Inc. – Materials may be reproduced for classroom use only.

This article is reprinted here with permission of the Association for Asian Studies, Inc.,

the publisher of Education About Asia (EAA). This article originally appeared in a

special section of Education About Asia, Vol. 6:3 (Winter 2001), a section that was

produced with the financial support of The Infinity Foundation.

While I was growing up I was oblivious of and somewhat indifferent to religious matters. During my childhood, secular figures like Mahatma Gandhi and Nehru (India’s first Prime Minister) were more important as symbols of inspiration than our vast array of devis and devatas (goddesses and gods). However, our deities do not presume to punish us, or even get angry with us, if we choose to ignore them. One can be an atheist while being an integral part of the Hindu community. The Hindu divinities issue no commandments.

They do not automatically retaliate by rejecting or threatening to excommunicate us if we live by our own code of morality rather than follow their precepts. And yet they have clever ways of quietly intruding into our lives and knocking at the doors of our consciousness. It is very common, for example, for a dutiful son to be praised as Ram (divine hero of the epic Ramayana) incarnate, or a talented daughter commended as a virtual Saraswati (goddess of learning and the fine arts). I have often heard a happy and satisfied mother-in-law refer to her son’s wife as the ‘coming of Lakshmi (goddess of wealth) incarnate’ into her home. One constantly meets the living incarnations of Hindu gods and goddesses in everyday life. Frequently their worldly behave-alikes are genuinely loveable and even inspiring in the way they live up to their chosen commitments.

Thus, Hindu devis and devatas are not distant heavenly figures, but a living presence in most people’s lives. They hold powerful sway as moral exemplars who demonstrate standards of morality that even ordinary people can aspire to emulate. But the codes of morality they demonstrate are not prescriptive. They are there to provide valuable insights into certain enduring values that people use in their own lives in an extremely flexible way, keeping the immediate situation in mind. Hindus usually do not fall into the trap of uncritically replicating the behavior of the deities they revere, for that would produce absurd or tragic results.

|

Saraswati India, state of Karnataka, Mysore ca. 1830-40 Victoria and Albert Museum |

|

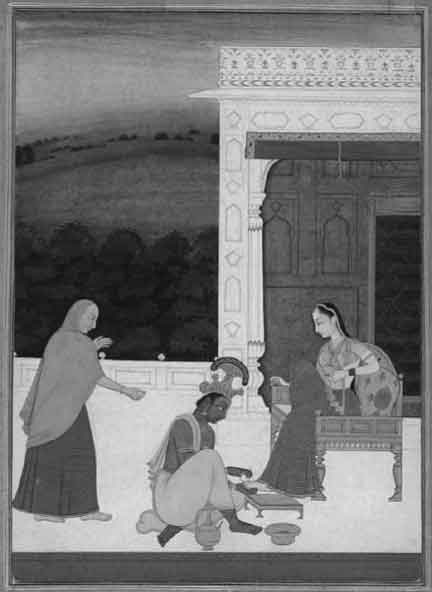

Krishna Washes Radha’s Feet Attributed to Nainsukh. India, Punjab Hills, Jammu, ca. 1760 San Diego Museum of Art: Edwin Binney 3d Collection |

| A special feature of Hindu sanatan dharma (immemorial, eternal moral code) is that there is no sharp divide between the divine and the human. Various gods and goddesses take an avatar (earthly incarnation) and descend to earth to appear among humans like ordinary mortals in intimate familial relationships. They are often willing to be judged by the same rules and moral yardsticks that one would use for a fellow human being. Devotees and non-devotees alike have the right to judge them by how well they perform or fail to perform the roles they have chosen. They neither claim perfection nor do they command us to unquestioningly approve of all they do. They allow us the freedom to pass judgements on them, to condemn those of their actions that we consider immoral or unfair, and to praise those actions we find honorable or worthy of emulation. For instance, Ram, as the avatar of Vishnu (the preserver in the divine trinity who appears in different incarnations in the human world) is revered as maryada purushottam (“the best of men”). He becomes worthy of reverence by proving himself true to his moral duties in diverse roles at great personal cost. He is an ideal son not only to his doting father, but even to his spiteful stepmother. As an elder brother, Our goddesses, like our gods, allow their devotees and non-devotees a great many liberties, including the freedom to demand responsive and improved behavior on their part, and also the right to rewrite and redefine their roles for them. That is why we have hundreds of known versions of the Ramayan and the Mahabharat(the two most important Hindu epics) and other religious texts. For instance, Lord Ram’s unfair treatment of Sita in the latter part of Balmiki’s Ramayan, first in demanding that she go through a fire ordeal (agnipariksha) to prove her chastity and yet abandoning her in a forest in an advanced state of pregnancy because of irresponsible gossip by some of his subjects, has aroused so much condemnation and kept people so upset over centuries that successive generations have made innumerable attempts to reconceive the narrative. One common feature of many of the latter day versions of the Ramayan, including the most popular of them all, the Tulsi Ramayan, is an attempt to reform Ram’s behavior to prove himself a more worthy husband for Sita, and thereby mitigate or undo the injustice inflicted on her in Balmiki’s Ramayan, which first put in writing the story of the injustice done to Sita. |

|

In fact, Hindus assume the right even to punish the gods for misbehavior or for failing to keep a pact. For example, Krishna (another avatar of Vishnu), as the son of Yashoda, has to take many a beating for playing naughty pranks on his mother and other women, like any ordinary child or adolescent. This right to punish gods is exercised not just in legends, but by ordinary people in real life as well. For example, in drought-prone villages of India, when rains are delayed, it is not uncommon to find villagers keeping the icon of the deity they worship submerged under water as punishment of the god until the rains actually materialize. Devotees withdrawing worship and food offerings to deities when they fail to respond to prayers is another common method of “punishing” gods.

Thus, while the celestial figures don’t claim special privileges on account of their divinity, human beings are allowed the possibility of being elevated to the divine, overriding gods and goddesses in matters ranging from valor to morality. An important route to divinity is also through bhakti (devotion)-not just to some god or goddess, but even to some human being. For example, Hanuman (the monkey god in the epic Ramayan) became worthy of worship, with special temples built to honor him, on account of his total devotion to Ram. Mirabai, the sixteenth-century princess turned saint-poet of Rajasthan, who violated all the norms expected from her as royalty, has temples built to commemorate her bhakti because she abandoned herself totally to the love of Krishna, whose stone image she accepted as her husband. Others have achieved divinity by being devoted sons or brothers. It is, for instance, common to hear grown-up men proudly declare: “In our family we worship ‘so-and-so'”-who could be an uncle, an elder sister or a grandmother. Or they may say with pride: “My mother is more important to me than any god.”

There are innumerable myths holding up as role models those who were revered by humans and gods alike for serving and worshipping their parents above any god. Among the most popular tales derived from the Shiv Puron, but now part of folklore, is this version I heard from my mother:

Once the various gods and goddesses got into a competitive mode to determine which of them should have his name invoked first at the start of any religious ritual. By consensus, they decided that the one who beat others in finishing a full round of the universe would qualify for this honor. So each one of them set out on their respective vaahans (mode of transport: for example, a lion for Durga, swan for Saraswati, varah for Vishnu, Nandi bull for Shiv, garuda for Vishnu). Since the vaahan of the elephantheaded god Ganesh happens to be a mouse, Ganesh knew that he did not stand a chance of winning the race, no matter how fast his vaahan moved. Suddenly, a bright idea occurred to him. He seated his parents-Shiv and Parvati-together and went round them seven times. Thereafter, he sat and relaxed, waiting for others to return. When the various gods and goddesses returned at the agreed spot, all tired and exhausted from the big journey, they were stunned to find that Ganesh had preceded them all and was waiting for them in a relaxed mood. “How come you are here first?” they asked in a surprised chorus.”Simple! My parents are the universe for me. I went around them, not once but seven times. So I have beaten you seven times over.” The gods and goddesses were defenseless before such an ingenuous answer and conceded the honor to Ganesh. Ever since, Ganesh’s name is the first to be invoked in all religious rituals and prayers.

|

|

The Varkari sect of Maharashtra which worships the god Krishna as Vitthal, whose defining characteristic is love for his devotees, has given popular currency to the following story to underscore that devoted service of one’s parents is higher than worship of any divinity:

Stories such as these powerfully reinforce one of the essential characteristics of Hindu culture: those who excel in performing their worldly duties with extraordinary commitment and love acquire power even over gods. So powerful is the hold of this ideology that even in contemporary Bollywood (India’s Hollywood) films, most of our heroes qualify for the hero’s status by passing through this essential test of willingness to sacrifice one’s own happiness for the sake of family and parents. But parents, too, are expected to be unconditionally loving, generous and forgiving in order for this worldview to prevail. Even when parents make unreasonable demands, as did Ram’s stepmother in the Ramayan, children are supposed to win them over by love and obedience, which is expected to bring agenuine change of heart. A certain kind of rebellion against fathers is still permissible, but close bonding with and unconditional obedience to the wishes of mothers is considered more sacred than respect for fathers (or for that matter any god) because mothers are seen as the living manifestation of shakti, the feminine energizing force behind the universe. Shakti The Energizing Force of DivinityOne essential tenet of Hinduism-pre-Vedic, Vedic and post-Vedic-is that shakti, the feminine energy, is believed to represent the primeval creative principle underlying the cosmos. She is the energizing force of all divinity, of every being and every thing. Different forms and manifestations of this Universal Creative Energy are personified as a vast array of goddesses. Shakti is known by the generic name, Devi, derived from the Sanskrit div meaning “to shine.” She is worshipped under different names, in different places and in different appearances, as the symbol of life-giving powers as well as the power to destroy creation itself. Epic and pauranic (writings from the period that followed the epics) literature gives a whole array of names and attributes to the universal feminine power, and the various goddesses take on distinct conographic forms. For example, as mentioned earlier, Sri Lakshmi is celebrated as the goddess of wealth and prosperity Saraswati as the presiding deity of the arts and learning, Usha as the goddess of dawn is the dispeller of ignorance, and Durga is the vanquisher of evil. Earth itself is worshipped as the goddess Prithvi. The knowledge aspect of the Devi is represented by a Shakti cluster of ten goddesses known as Dasa Mahavidyas-the Ten Great or Transcendental Wisdoms-which encompass the entire universe of knowledge. Their consort gods are placed much lower in status and power. The energy of god is feminine, and almost every god is static-even dead-without his shakti. But shakti is complete in herself because her existence does not depend on any extraneous force. The male gods are incomplete without a consort, even powerless, barring rare exceptions like Dattatray, who also remained single. But the goddesses become even more powerful in their non-consort avatars. When the energies of male gods prove inadequate, they have to turn to the female for protection. |

|

|

Devi Battles Buffalo Demon Mahisha India, Punjab Hills, Chamba ca. 1830 Source: Devi the Great Goddess: Female Divinity in South Asian Art, published by the Arthur M. Sackler Gallery in association with Mapin Publishing, Ahmedabad and Prestel Verlag, Munich. Copyright ©1999 Smithsonian Institution |

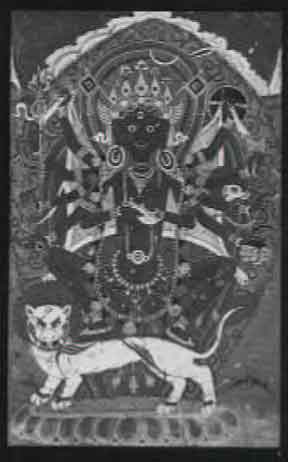

For example, the great goddess Durga was born from the energies of the divinities when the gods became impotent in the long, drawn-out battle with asuras (demons). She needs no male to legitimize her power, nor is she dependent on the need to conciliate any male divinity. In her Mahakali roop (destructive manifestation of the great goddess), she is awesome, ruthless and completely uncontrollable. Her battle represents a universal war between knowledge and ignorance, truth and falsehood, the oppressor and the oppressed. But she also promises that as Sakambhari she will nourish the world in time of need with the vegetation grown from her own body, and that in her terrible form she will deliver her worshippers from their enemies.

Thus the manifestations of the Devi are in response to different requirements and times. The allpowerful feminine force assumes diverse forms, taking different avatars to fulfill diverse purposes in changed circumstances and time periods. Sometimes she is frightening and even vengeful, like Chandi; often she is like Parvati, who as the nurturing mother figure constantly guides her husband to be generous and benevolent towards his devotees; an ideal daughter, wife, daughter-in-law, and a compassionate, forgiving mother figure like Sita; a dominating and demanding wife like Draupadi; or a besotted beloved like Radha.

Freedom to Create New Deities

Even though goddess worship is a living and growing tradition in India starting as early as the Harappan culture of 3000 B.C.E. (if not earlier), there has been a good deal of fluctuation in the fortunes of various goddesses. Some ancient ones have continued to hold sway, and others have lost some of their pre-eminence. While some reappear as newer versions, there are also instances of brand new goddesses being invented. Two examples of such new births are Bharat Mata and Santoshi Ma. Bharat Mata was invented in the late nineteenth century during the freedom movement to represent the enslaved Mother India calling out to her sons to free her from colonial bondage. Santoshi Ma represents contentment. She does not find mention in any of the traditional texts but gained popular currency thanks to a Bollywood film released in the early 1970s called Jai Santoshi Ma (Hail, Santoshi Mother).

Santoshi Ma combines some of the qualities of non-consort goddesses with those of consort goddesses. The shakti form of goddesses come to the aid of human beings and gods in periods of cosmic darkness by killing the demons who threaten the cosmic order. But Santoshi Ma, being a modern goddess, does not establish herself by annihilating any particular demons. Instead, her miraculous powers come to the rescue of her devotees who are being harassed and tyrannized by fellow human beings. She is particularly popular among women who observe fasts on Fridays as symbolic penances in order to achieve their desired goals in this life-be it finding a good husband, wealth in the family, or general contentment.

I often say it jokingly – but the statement itself is serious – that we could solve all the financial problems of Manushi by building a shrine to Manushi devi – a new goddess who would combine the qualities of Saraswati, Durga, Joan of Arc, and more. In other words, Hindus are free to create new gods and goddesses, and bestow on them attributes of their own choice.

The Hindu deities thus enter into intimate kinship types of relations with their devotees. The deities accept gifts and devotion, but in return are also expected to grant wishes and give boons. The human-god relationship is collaborative as it is among kin where there is regular exchange of gifts. Even affection and loyalty are expected to be mutual. The ishta dev or devi (personal deity) is expected to come to the rescue of the devotee in times of need, just as relatives are supposed to do all they can to lend a helping hand in times of distress.

|

Kali embodying the energies of creation and dissolution Nepal, c. 17th century Source: Kali: The Feminine Force By Ajit Mookerjee |

Ascent from Human to Divine

Every village in India has its gram devi or devata (village deity). The gram devatas are usually connected with extreme piety, but many of the myths of gram devis tell us of ordinary human women who rose in rage because they were cheated or sought to be ravished by some evil male. Out of such desecration, they rise in terrible fury and thereby grow in stature to span heaven and earth. Their power of destruction, born out of righteous indignation, terrorizes everybody into submission. But once their rage has achieved its purpose and when devotees are ready to propitiate them, they can be relied upon for protection from enemies as well as for healing of both physical and psychic illnesses. Theirs are myths of ascent from human into divine forms, rather than of descent from divine to human.

Any woman who manifests extraordinary strength and is believed to be her own mistress and totally unafraid of men begins to be treated with special awe and reverence, often commanding unconditional obedience in her own milieu and treated as a manifestation of

the goddess Durga. Indira Gandhi, India’s first woman prime minister, was often referred to as Durga incarnate, because all her male colleagues were mortally afraid of her and rarely dared challenge her commands. She began to lose her hold only after she let it be publicly known that she had become dependent on her younger son, Sanjay, who was beginning to call the shots in politics and governance. Women of even humbler origins have this choice. For example, India’s first woman police officer, Kiran Bedi, is an all-India cult figure and is often referred to as a Durga because she, too, projects the image of a woman who can outperform men in every way and is fearless even in dealing with criminals.

One comes across such mini-Durgas all over the country. Every other village and urban neighborhood would have some such women who command respect and deference, at least within their own kinship group, if not in the public domain. I remember as a child, whenever I got into one of my righteous rages, my mother would warn others, saying: “Don’t provoke her into manifesting her Durga-Chandi roop.” Thus, very early on, family friends and relatives understood that it was best to be careful about stepping on my toes. Even without being a Durga devotee, I unconsciously began to successfully “play Durga” in dealing with a whole range of situations, from sexual harassment to intervening between two groups of riotous men, to bringing under control neighborhood drunkards and wife beaters.

Varied Manifestations of the Feminine

The range of moral exemplars available to Hindu women is indeed spectacular. Apart from goddesses who work hard to win respect as wives, at the other end of the spectrum are those who consider it an affront that any male should dare consider them sexually accessible or that they would condescend to be mere consorts. Radha’s complete abandonment to her extramarital love with Krishna is no less deified than Sita’s steadfast devotion to her husband Ram. Yet another category of women exemplars are those who spurn the bond of matrimony, either by refusing to get married at all despite social expectations, or by disowning the marital relationship after being forced into it for awhile. Almost all the women saint-poets of India, around whom grew powerful religious cults, chose to either walk out on their husbands or never got married. Avvai, the ancient saint-poet of South India, resolved the dilemma of young womanhood by seeking a drastic solution in order to avoid marriage: she prayed to her deity to end her youth and beauty. Immediately she was transformed into an old woman and thus released from the requirement of marriage. Andal, the saint-poet of ninth-century South India, refused to marry and declared herself the bride of Krishna. Akka Mahadevi was forced to marry a chieftain. Legend goes that she told him that she would leave him if he touched her three times against her will. He does so, and she leaves him. In the course of her spiritual wandering she even throws away all her clothes. Lal Ded, the fourteenth-century mystic poet of Kashmir revered alike by Hindus and Muslims, was trapped in an unhappy marriage and saddled with a tyrannical mother in-law. She too left her matrimonial home, shed her clothes and became a wanderer, singing and dancing in ecstasy. Muktabai (1279-97) whose name itself means “liberated,” also avoided matrimony. Meerabai, the sixteenth-century saint-poet of Rajasthan as well as Bahinabai (1628-1700) of Maharashtra, like Lal Ded, gave free vent to the suffocation and tyranny they experienced in their respective marriages. Most of these women became roving mendicants rising above all social constraints imposed on women in the name of family honor. The nudity some of them practised was an assertion of their refusal to abide by social norms and conventions with regard to a woman’s role in society.

I remember that when as a child I read the stories about Meerabai, I wasn’t quite able to grasp the meaning and power of bhakti. I was, however, much inspired and influenced by what appeared to me a clever ploy on her part in getting herself married to a stone image of Krishna and using him as a shield against the demands of her real-life husband. A stone image cannot order you around, dictating do’s and don’ts, the way a human husband can. In the name of devotion to Krishna, she acquired the right to go where she pleased, when she pleased, intermixing freely with people of all castes and classes. She sang and danced in public and declared herself beyond the restrictive norms expected of a Rajput queen. My interpretation is not too far fetched, given that I saw the living example in one of my grand-aunts who, in her own way, did many of the things Meerabai had done – though out of very different compulsions. She was a fashionable socialite in her youth, but was married to an unsociable, scholarly type of man. Marriage with him was too dull an affair for her. So she adopted the white robes of a sanyasin (ascetic) and took to singing devotional music. Her bhakti songs brought her numerous invitations from near and far, from the wealthy and the poor. That gave her ample opportunities to travel on her own, build friendships and enjoy the hospitality of a vast range of people who invited her for singing bhajans (devotional music)-all this without invoking any social stigma. The whole family understood that her bhakti was in response to an oppressive marriage, but she did not suffer the censure she would have, had she followed the same free and roving lifestyle without adopting a Meerabai-like persona.

|

|

| Meerabai thus became a symbol of feminine freedom in my own life, though devotion to a deity of the Meera variety is not the route I could choose with any honesty for my personal freedom. I interpreted her life to mean devotion to any idea which is larger than yourself, including devotion to a social or political cause. Gandhi, for instance, translated Ram bhakti to mean working for the freedom of his motherland and an exploitation-free life for farmers, for lower castes, and women. My own life and that of many other women confirms over and over again that once people in India are convinced of your commitment to a higher cause and your strength to live by it – be it religious, social or political – you can break out of all the restrictions meant for ordinary people with impunity, and yet be respected for it.

For women who wish to opt out of matrimony altogether, the lives of non-consort goddesses and women saint-poets create a unique kind of a social space in our otherwise marriage-obsessed culture. This has also made voluntary celibacy a very respected choice for women in India. In many modern cultures, especially those influenced by Freudian theories, sexual abstinence is seen as an unhealthy aberration that is supposed to lead to all kinds of neuroses and a disoriented personality. In India, however, we are still heavily inclined towards the opposite tradition that holds that purposeful and voluntary sexual abstinence bestows extraordinary powers on human beings. Any woman who, like Durga, becomes sexually inaccessible, consort of none, nor in search of a consort, tends to command tremendous awe and reverence in India, especially if she devotes herself to a larger cause. Many of the most revered women in Indian history opted out of sexual relations altogether. They have been treated as virtual goddesses for demonstrating such firm resolve, so much so that gods come to fear and are compelled to do the bidding of such women. During the nineteenth-century social reform movements, and even more so during the freedom movement led by Gandhi, many of the male leaders exhorted women to follow the example of Meerabai, who chose to follow the call of conscience rather than the beaten track of matrimony. A large number of women who became active in these movements were thus encouraged and chose to stay single. In the tradition of non-consort goddesses, many came to be treated as symbols of feminine power in their respective regions. |

|

Hindu Deities Know Peaceful Co-Living

While Hindu deities are not permitted to be jealous gods demanding exclusive loyalty from their devotees, the latter do occasionally come into conflict with each other, as for example the historic clashes between Shaivites and Vaishnavites (devotees of Shiv and Vishnu). There are no comparable ego clashes between various goddesses or their devotees. Goddesses do occasionally get into competition with each other over who is more virtuous or whose husband is more powerful. But such stories invariably end with their reconciliation and acceptance of each other’s worth. Overall our goddesses believe in peaceful co-living, in graceful acceptance of each other’s worth rather than claiming or establishing superiority over each other. For example, a martial goddess like Durga does not consider herself superior to a pacifist sufferer like Sita. Nor is Radha treated with disdain for being lost in Krishna’s love despite his polygamous dalliances. It is accepted that they represent many aspects of feminine behavior, and diverse responses to similar and varied situations. Therefore, devotees of one are not expected to disparage other manifestations of the same goddess.

The numerous Hindu shastras (scriptures) repeatedly emphasize that codes of morality have to be time and place and even person specific, that they must evolve with the changing requirements of human beings. Hence there is great variation between different shastras and smritis (remembered tradition) produced in different regions at different times. Keeping that in view, our gods allow us to rework our responses according to the changing demands of the times. They have successfully lent themselves to numerous social causes and become powerful allies even in contemporary movements for social justice. They are accepted with ease in those new roles even by their traditional devotees, provided the devotees are convinced of the sincerity of the effort and the good faith of the alliance-seeker.

To illustrate again from the example of Sita, who continues to be the most popular icon and role model for women: while for many, Sita is the symbol of wifely devotion, Mahatma Gandhi used the Sita ideal as a symbol to promote women’s strength, autonomy and ability to protect themselves, rather than depend on men for safety. His Sita was like a “lioness in spirit” before whom demon king Ravan became “as helpless as a goat.” For the protection of her virtues, even in Ravan’s custody, she did not “need the assistance of Ram.” Her own purity was her sole shield. Ravan dared not touch her against her will. Gandhi’s Sita was “no slave of Ram.” She could say “No” even to her husband if he approached her carnally against her will. Gandhi’s message that women had the right to define and follow their own dharma (code of morality) rather than be constricted to wifehood brought hundreds of thousands of women out of domestic confines into the political arena. He wanted to create a whole army of new Sitas who were not brought up to think that a woman “was well only with her husband or on the funeral pyre.” Gandhi’s Sita also became a symbol of swadeshi or decolonization of the Indian economy. He asked the women of India to follow her example and wear Indian homespun, and boycott foreign fineries because his Sita would never wear imported fabric. Gandhi’s Sitas were encouraged to break the shackles of domesticity, to come out of purda, to lead political movements and teach the art of peace to this warring world.

| Gandhi often admitted that he learnt his first lesson in satyagraha from women like his mother and wife, both of whom were indeed Sita-like in their steadfastness and commitment. The essence of satyagraha (non-violent, truth force) lay in securing a moral victory over one’s opponent by winning over his heart rather than vanquishing or humiliating him, as well as gaining the sympathy and support of all those who witness the conflict. That is exactly how his favorite heroine, Sita, managed to be one-up on Ram. Gandhi, too, designed his movement to ensure that he got sympathy from all in his battle of right against might.It is noteworthy that even orthodox or conservative Hindus did not oppose or condemn his radical and innovative use of Sita as a role model for Indian women, because the right to interpret traditional texts and attribute meaning to gods and goddesses belongs to each devotee. People in India have used this right with abandon throughout history, thus giving Hindu religion and culture extraordinary versatility and ability to adapt to diverse situations. |

|

Madhu Kishwar is a Senior Fellow at the Center for the Study of Developing Societies in Delhi, and the founding Editor of Manushi – A Journal about Women and Society, as well as founder of Manushi Nagrik Adhikar Manch (Citizens Rights Forum).