Audial and Literary Cultures: The Bhagavad Gita as a Case Study

Audial and Literary Cultures: The Bhagavad Gita as a Case Study

by Antonio T. de Nicolas, PhD

I am arguing in this paper that in order to study cultures we must first be able to identify the models by which a culture forms itself. I distinguish. between audial and literary cultures and audial cultures I further distinguish from oral cultures. Oral cultures used songs to transmit information (like the navigation rules of the Somoans), while an audial culture provides us with a structure ruled by the corre- spondence between the innate auditory sense of harmony and tone on the one hand and the arithmetic properties and ratios of the vibrating strings on the other. The literary culture takes the eye as the primary sense and organizes sensation by the criteria of a semiotic model that takes sight as primary. These texts are based upon the properties of sentences as embodied in grammar, two-valued logic, mathematics, classical physics, constructivism.

Through the identification of culture with Text and by using the Bhagavad Gita as a case study, I am able to isolate the three following texts from this original audial Text: (a) a semiotic text, alien to the Gita. and identifiable. as the text the reader carries with him/her to the reading of the Gita; (b) an audial/musical text, or the text-model by which the Gitai, so to speak, wrote itself; (c) the text of the imagination, or a text based on non-cognitive skills for the sake of decision-making; this text we identify as the text of meditation.

While the literary or semiotic text is grounded on principles of knowledge and therefore on abstraction, the audial/musical text and the meditation text are both grounded on the imagination and therefore on experience. Thus we establish two origins of language: cognition and imagination. Each develops different skffls and the rules of reference are complementary in the sense that what is true or can truly be said in one is not true and cannot truly be said in the other.

This paper concentrates in developing the audial/musical model. It shows, in two appendices, the dramatic consequences it carries for translations, transliterations and the transformations of the imagination.

Introduction

This essay is a prelude to the study of culture. It will not deal with the ‘facts’ of cultures, but rather the conditions of which cultural facts are born. ‘Culture’ is often equated with language, for language is the empirical evidence of what we call a culture and culture is only knowable as language and through language as some form of ‘human flesh’ and vice versa. What is here called human flesh is the embodiment of a plurality of languages from which a plurality of cultures may be abstracted. Thus, language as understood here will take into account not only the external tokens of sound, gesture and word, but also the internal tokens of intentionality, conceptualization and purposive action. I shall therefore focus not only on language as culturally used but also on the presuppositions which such use entails.

In order to do this successfully, we have to recall from the cemeteries of the centuries a discipline that has long been dead to the memories of man: music as epistemology. When studying other cultures, natural science and even philosophy have approached those cultures on the assumption that their disciplines provided a knowledge radical enough (equal to the roots) to coincide with the knowledge that grounds culture, especially audial cultures. Philosophy’s study of culture has committed the same sin of interpretation by identifying radicality with epistemology and epistemology with a theory of knowledge. In every case the particular form of knowledge of the discipline determines the ground of the culture under study. What remains problematic, therefore, is the fact that the ground of knowledge of natural science, philosophy, but especially of audial cultures, is not ‘knowledge’ at all, but a bundle of presuppositions, criteria and decisions which remain mute once knowledge is established. Therefore, the word epistemology will be used to focus exclusively on those criteria and presuppositions underlying the audial cultures that took sound as the source of their criteria of knowledge. Music will refer only to the music that has served as a model to derive epistemological criteria, and not to the convenient meaning of music as an art form that has had a history. I shall test this thesis on a well known document of the Hindu tradition: the Bhagavad-Gita,* which we shall call the Text, with a capital T. This hermeneutic approach will, however, apply to all cultural languages and their translations and transliterations.

*The translations from the Sanskrit are my own. Philosophy as radical activity is developed in my book: Avatara: The Humanization of Philosophy Through the Bhagavad Gita (New York: Nicholas Hays, 1976). The model of language by the criteria of sound is fully developed in my book: Meditations Through the Rg Veda: Four Dimensional Man (New York: Shambhala/Random House, 1978), and this language is verified by Ernest G. McClain in his books: The Myth of Invariance: The Origin of the Gods, Mathematics and Music from the Rg Veda to Plato (New York: Shambhala,/Random House, 1978), The Pythagorean Plato (New York: Nicholas Hays, 1978) and Meditations Through the Quran (New York: Nicholas Hays, 1981).

To help the reader cope with this essay, let me advance here some of the presuppositions/ conclusions on which it is based.

Cultures divide into at least two recognizable groups: oral/audial and literary or logomachic.

Oral/audial cultures or texts are ruled by the correspondence between the innate auditory sense of harmony and tone on the one hand and the arithmetic properties and ratios of the vibrating strings on the other. They also possess inner mandalas, or protogeometries homologous with musical arithmology charting the path of the imagination.

An audial culture or text takes the ear as primary sense and organizes sensation and the criteria of interpretation or of knowledge by the criteria of a model based upon certain demonstrable criteria of sound properties.

The literary culture or text takes the eye as the primary sense and organizes sensation by the criteria of a semiotic model that takes sight as primary. These texts are based upon the properties of sentences as embodied in grammar, two-valued logic, mathematics, classical physics, constructivism. Such texts tend to reduce all issues, all languages, to one or another form of logomachy: disputes about words, their meanings, relationships and implications. Several elements contribute to establish certain variable criteria as fixed or invariant. The invariant criteria determine the reading or the listening. The process by which certain criteria become invariant is the process of verification and it is always in the hands of one or more sciences. In the case of oral texts, the sciences that formed and verified the invariant criteria were music and acoustics. In the case of literary texts the invariant criteria were fixed by a logic, physics, geometry and optics. Any culture or text which would not take these sciences as the method of verification was never considered a ‘text’ or a ‘culture’ and was automatically exiled to the limbo of preliteracy or subcultures.

What we normally call prose is the sediment of many scientific and non-scientific, audial and logomachic translations and transliterations of these texts and subtexts. In the wake of scientific verification philosophers and others followed with justifications of what had already been verified and epistemology was equated with a ‘theory of knowledge’. Depending on the science of the times philosophers were mostly mathematicians, physicists, theologians, biologists or musicians.

Since prose was the sediment of so many conflicting epistemologies, philosophy has always been much more an exercise in power than in reason. The philosopher was more keen on converting people to his own model of reason than in liberating his own model of reason from its own conditioning and conditioned invariant criteria.

Nowhere has this philosophical lack of reason been more keenly felt than in the reading of texts ruled by audial criteria. The language of the imagination is such a text regardless of whether it comes from the East or the West.

The poet, the singer, the mystic is always straddling the frame of a model, challenging it, transcending it, or simply repeating it, once more with feeling; but unless the reader knows the frame the poet, the singer, the mystic is riding, he might be climbing or barking up the wrong leg. There is always a necessary connection between texts and models. And the reader has no freedom but to find it.

To jump the common frame, however, entails always a risk. Besides the common misunderstanding, mystics divide on this point. Some aim for the absolute Zero: the absolute, ineffable experience – Buddhism, Meister Eckhart, John of the Cross – while others are content with aiming for the One: the Incarnation – Hinduism, Ignatius de Loyola. Some would like, even demand, that at the other end of the frame there be nothing, absolute emptiness, but all they really find is yet another frame and another, and another. Nirvana equals Samsara, freedom equals controls. Movement through frames is a necessary condition for detachment and freedom.

When facing, therefore, a text from an audial culture we are forced to overcome the following problems:

(a) the language/model we carry with us to interpret the document:

(b) the multiple language/models the Text offers for its own possibility of existence: (the fact that by those language/models it wrote itself, so to speak);

(c) the most difficult realization of all is that any Text from an audial culture demands from us the ability to re-enter a whole different communications-system not only different from our own but demanding from us certain activities for which we may not even be trained or be able to handle.

Thus, the Text of The Bhagavad Gita offers us three texts for our consideration. One text for translation, and this we shall consider in Appendix II; a text for transliteration, the musical model, and this we shall consider in Appendix I; and finally a text for meditation, and this we shall consider in Appendix III. These three texts, as derived from the Text, have their genetic origin in the imagination. They are made and remade by the use of the imagination, with the aid of memory. They are not texts built on cognitive skills, and thus their rules of reference differ. Since we cannot do justice to the three texts in this paper we shall concentrate on the text for transliteration and refer the others to the Appendices. It would be useful to bear in mind that since texts built on cognitive skills and those built on imagination make claims about knowledge that we reserve the word wisdom to those texts only that derive from the imagination, or texts from audial cultures.

In view of the above we will focus the present study of the Citff in the following three moves:

I. The language of prakti/karman (the primacy of sensation, substances).

II. The language of dharma/Krsna/purusa (the primacy of fields).

III. The model of both languages (the primary of movement, detachment and embodiment).

Samjaya, the narrator of the Gita, designates for us as the world of the Gita as a world embedded in sound, mounted on the wheel of sound and ruled by its criteria. The whole ‘body’ of the Gita stretches as far as its sound can be heard. Notice how the Gita begins amidst noise and a chaos of sound and how, from a distance, Samjaya is able to ‘pick out’ the dialogue between Krsna’s ‘word’, a word which has been moving among confused sounding noises, yet remains always clear throughout. Notice also that the cultural ground from which Arjuna and Krsna emerge is a world of ‘sounding silence’, the original rhythmic impulse which keeps sending beings and worlds without ever being exhausted. By which criteria do these sounds become the language of the Gita?

I. The language of prakrti/karman (the primacy of sensation, substances)

According to the Gita, Arjuna, as a Hindu warrior, should know not only to act (fight) without regard to the consequences of his action according to his condition (XVIII. 45), but he should also know how to act without any doubt (IV. 40; VI. 39; VIII. 7) and with an unshakable judgment (XVIII. 49). Arjuna, however, collapses in the battlefield unable to balance the terror of being a man with the decision to be a man. The terror is grounded on the belief that there is a natural condition of man, a natural self-body, which naturally and blindly is forced toward the reproduction of social action. Arjuna’s liberating decision will be his ability to recover the cultural condition of man: man having to cope with a multiplicity of predetermined worlds (karmic laws) of which he can not only sketch the profile (dharma, horizon, context), but must also make his self-body coincide with its direction and demarcations. Language and body coincide.

To follow systematically this journey from the space and self-body of crisis to the spaces and self-bodies of liberation, let us summarize here the programmatic moves of Krsna/Arjuna.

(1) Arjuna’s arguments for in-action in the present situation are futile once he is in that present situation in the field of battle (dharmaksetre).

(2) These arguments veil a belief in a natural, raw, barbarian state within which man may try to hide, as it were, neutral and unaware of ontological and epistemological presuppositions: the slave of karmic laws.

(3) This false situation of Arjuna is held together (epistemologically and ontologicauy) by the bewitchment of language in the form of ahamkara (I-maker or sense of I) and its subsequent epistemological and ontological appropriations or identifications. A linguistic space is thus absolutized into a universal human space reducing all human acting and human self-body to only one possible interpretation.

Situation as determined action

Krsna shows Arjuna that his arguments for not doing anything while facing the battlefield are useless and ineffective. He shows him that to fight (act) is inevitable. He points out that according to the Ksatriya tradition fighting is in keeping with the noble traditions of the royal sages; it is also virtuous, enough to lead to heaven, and it is glorious enough to establish fame on the earth. Thus it is emphasized that this line of action has come down through tradition (IV. 2). Winning or losing, participation in war, would accomplish good in either case (II. 37), and Arjuna is therefore clearly told: ‘But if you will not engage in this righteous battle, then having foresaken your own particular dharma as well as glory, you will incur sin’ (II. 33).

In this further attempt to show Arjuna the emptiness of his arguments not to fight, Krsna, as one who has the whole culture at a glance, reveals before him the destiny of the people assembled there for the battle and points out that it is futile on his part to think that merely on account of his desisting from fighting, the battle would be avoided and the lives of these people would be saved. In keeping with the line of argument that the evil-doers are killed by their own outrageous conduct and the man who is merely instrumental in their killing is not guilty of the sin, Krsna exhorts Arjuna to follow his duty and earn the glory of a true warrior (XI. 32-33). Arjuna is told to be wise enough to realize the true duty of a Ksatriya, with the natural endowment of which he is born, and not to allow his I-maker (ahamkara) and attachment to get the better of him (III. 30).

Had Arjuna minded the tradition, and remembered even a bit of its intentionality, he could have avoided this impasse (II. 40). Arjuna’s condition as a warrior is grounded on ‘heroism, energy, firmness, resourcefulness and not fleeing in battle; generosity and lordliness …’ (XVIII. 43), and in a ‘battle situation’ there is nothing else he can choose.

Despite this, Arjuna, even in his despair, realizes that human acting is decision-making, a decision in relation to a radical orientation of knowledge in which the whole body participates, a judgment at every step of the way without questions, doubts or hesitations. He wishes he knew how to be a man or asaktabuddhi (firm knowledge-wisdom) (XVIII. 49; II. 41; II. 54).

Krsna promises him no less.* But first Arjuna must realize and transcend the muddy space in which he is trapped. The important point to be made, however, is that a rationalization of in-action (or of whatever action man performs) is always an interpretation – radical and sufficient or dogmatic and insufficient – of a man’s orientation to life.

*see II. 67, 71; 73; XII. 8; IX. 34; IX. I; III. 32; IV. 40; VI. 39; VII, 21; VII. 7.

The relation dharma-karman and yoga

The first chapter of the Gita places man in the midst of his own authentic reality: despair, anxiety, inaction.

The second chapter shows the ground on which man (Arjuna) stood all his life: a theoretic consciousness of his culture and the actions and roles he was determined to play and for which he was trained by the culture. Now that this ground is no longer under Arjuna’s feet, what is he to do?

Chapter III offers the first solution: Arjuna must recover his lost memories, all he has forgotten: the kind of knowledge that created the culture in the first place, and the kind of knowledge that, if sought diligently, will help Arjuna save himself and his circumstance. T’he relation dharma-karman and yoga is the root relation which Arjna must discover to lead him to freedom.

The first line of the Gita identifies for us the human problem of Arjuna. The ‘field of battle’ and the ‘field of dharma‘ are the same: ‘dharmaksetra kuruksetra‘. In the field of the Kurus, in the field of dharma, the crisis of Arjuna unfolds. What is at stake in Arjuna’s mind is not the battle alone, but his whole social and conceptual scheme, his whole life: every action from fighting in battle to eating leftovers. He has literally no ground to stand on (I. 40-44). The root of the word dharma, dhr, means to support, sustain, hold together; i.e. dharma is the general or particular context and structure which holds together certain objects with definite and determined programs of action.

What constitutes, in the Gita, the basic element of our – or Arjuna’s – creatureliness, our historical ground is karman: ‘Karman is the creative force that causes creatures to exist (as creatures)’.* The word karman is a noun meaning action, from the root kr, ‘doing, acting, performing’. The significant point of the Gita, however, is not so much to stress this obvious fact of man having to act, but rather the fact, as in Arjuna’s case, that acting enslaves, if karmic acting brings along karmic thinking and its point of view on the world. Karmic thinking in this case consists in Arjuna or anyone thinking that he is the agent (III. 27; cf. XIII. 29); that is, he deludes himself into thinking linearly by causally uniting action after action and ontologically linking them with himself. In this view action, self, and body are unified ontologically; fear, anxiety, despair, agitation, in-action follow. Negatively the Gita says: ‘He who thinks himself the agent is wrong’ (XVIII. 16). There are five factors which are the causes of action (XVIII. 15), and, prakrti (as well as the gunas) are bound to lead you to action (XVIII. 50). Under karmic law man has no other alternative but to act. This sounds like sheer determination and it is. And although prakrti and the gunas may explain the human fact that man, whatever his nature, tamasic, rajasic or sattvic, has to act, they also put man in the midst of his own existential anguish that he is determined to act, trapped in action. Add to this inescapable fact man’s own decision to identify himself with his actions and you have the impossible aporia, problem, non-exit of Arjuna. Ths solution, obviously, is not in action but in the viewing it is grounded on. The starting point of Arjuna’s liberation is the understanding of dharma.

*See VIII. 3; in other contexts, see also II. 42-43; II. 47-57; III. 4-9; III. 14-15; III. 19-20; III, 22-25; IV. 14-24; IV. 32-33; V. 1-14; XVIII. 2-25.

Krsna addressing Arjuna, reminds him that his conduct does not become him (II. 3) and Arjuna confesses plainly that he is confused about his dharma (II. 7), and in typical karmic- value thinking asks the question (determined in the answer): ‘which would be better, tell me decisively (to fight or not to fight)’ (II. 7); he sees no other possible avenue of action.

All actions are action, and actions are of value, because they come so ordered in a concrete contextual-structure of dharma (V. 15; XVI. 19; IX. 16, 24). Looking at the actions alone, one is determined; knowing the dharma one is free. If we took directly at the Gita we find that Arjuna’s journey into his own culture from Chapters II through X is a journey of the relation between karman-dharma, action-context: cultural man and his multiple embodiments begin to emerge.

Two readings

If we were to read Chapter I of The Gita by the conditioning of a model of language that takes language as a sign, we would then of necessity focus on Arjuna’s body as a substance to which the attributes of sin, guilt, fear, despair must be ascribed. This self-body, moreover, will remain constant. This reading will force us to feel the weight of all the names, discreet noises, entities, in Chapter I of The Gita, and in general believe that each self-body is already endowed with agency and finality.

There is, however, another possible reading of the same chapter. When we see Arjuna’s limbs become weak, his mouth dry up, his body tremble, his hair stand on end, and the like, we are seeing a self-embodied theory collapsing. Agency and finality belong to this theory. What appears through Arjuna’s body is a theory made flesh which collapses because it does not account for the whole situation. The theory appears insufficient in the field of battle through Arjuna’s self-body. This is the yoga of crisis in Chapter I of The Gita.

Methodologically the two readings are incompatible. The first one takes a theory which is historically public and posterior to The Gita and universalizes itself to reduce the world to linguistic uniformity. On the other hand, the second reading proceeds by squeezing out of a particular and historical human flesh and circumstance the theory by which it becomes such flesh. Flesh and theory are inseparable like Arjuna and Krsna in the yoga of crisis of Chapter I in The Gita. Sensation is a language.

II. The language of dharma/Krsna/purusa (the primacy of fields)

When a man is in the midst of a crisis, like Arjuna’s, things must first get worse before they get better. The crisis must peak before it is resolved. Arjuna realizes in the midst of his impotence that his crisis is about knowledge: ‘Why is it not wise for us, O Janardana (Krsna)’? (I. 39). Arjuna realizes so vividly that his crisis lies in his position about knowledge that he is ready to give up victory, pleasure, his kingdom and even his own life for the sake of the knowledge that will take him away from his crisis.

Arjuna shares with his enemies the same theory of knowledge for which he blames them. Like the Kauravas, he does not see how things hang together on account of the greed of his mind for his own way of knowing (I. 38). Like them, he does not give up this delusion (II. 52; VI. 13) and the desire (II. 55; III. 37) born of this attachment. Attachment, fear, anger (II. 5 6) and hatred (XVIII. 51) are all born of desire which is ontologically linked to a theory of knowledge which can only function through self-identification and appropriation (II. 62; III. 37, 38). Both Arjuna and his enemies are ignorant of the fact that desire ontologically links man to the dualities: cold and heat, pleasure and pain, happiness and grief, knowledge and ignorance (II. 14, 15), good and evil (II. 57), and this they presuppose to be the knowledge of how things really are. The Gita, however, points out that this position is deluded since it is a knowledge covered by ignorance (V. 15), and in general it functions through the belief that an individual, (Arjuna) is the doer of the action (XVIII. 17; III. 27). In contrast, knowledge, according to The Gita, should produce even mindedness in pain and pleasure (see II. 15, 56; XII. 13, 18; XIV. 24), in honor and dishonor (XII. 18), in blame and praise (XII. 19), equality to friends and foes (XIV. 25), and in general a man without doubt and of firm judgment (II. 58).

By way of the radical thinking we have set before us, we find ourselves from the beginning of The Gita facing moving bodies and structures: each structure a rhythm through which a body-world appears, revealing as it appears a background of living beings together with the glory and terrors of their life. It is against this cultural horizon that the moving bodies of Arjuna and Krsna speak out and make present their world. Their movement in The Gita is the movement and opposition of the gunas. It is the movement and complementarity of prakrti and purusa. It is also their parity and dependence. Arjuna and Krsna are like two halves of an orange belonging to a common origin which negates and reconciles the parts in every movement. Yet, having this in mind, we may speak of Arjuna and Krsna as if the two halves were really independent. When Arjuna moves Krsna moves, and if Arjuna stands still so does Krsna.

One must not forget that Arjuna is a warrior, used to living dangerously, with death stalking him at every step. Yet it is this same Arjuna who is now in the grips of a crisis so severe that his limbs tremble, his skin is feverish, his weapons fall from his hands, and he can hardly move; the man has frozen. This is the problem which The Gita is ‘set’ to solve. It is a controlled experiment with sickness, diagnosis, medication, cure and rehabilitation, all in 700 verses, all in one song-poem. If Arjuna’s point of view depends for its survival on the objects and the senses as appropriated by the ahamkara and himself, the whole program of The Gita will be a program to desensitize such a world-view from its absolutized directions: to detach the senses from one absolute form of sensing and feeling the world. A man, to be a man, has to be able to move without touch, smell, taste, sight, noise; to be able to move up and down, backwards and forwards, in and out the corridors of his own emptiness into the throbbing light, the sustaining ground, by his own impulse. Man can only know his bearings if he himself becomes those bearings.

Arjuna’s initial condition in The Gita is a complete blank. He is tamas, dullness and inertia. It is not the case that Arjuna ‘feels’ low. Rather it is the case that Arjuna is the whole tamasic condition, not only in his mind but in his whole body-feelings-sensation. Man is viewpoint. Structure is the viewpoint made flesh. Arjuna is tamas and prakrti in Chapter I of the Bhagavad Gita.

If Arjuna had been able, in his moment of crisis, to realize that his body was as large as his tamasic condition, i.e. if he had been able to realize the dependence of body-feelings on perspective and realize also this ontological unity, then the subsequent journey of The Gita would have been superfluous. But Arjuna settles instead for a crisis and The Gita’s wheel moves on.

The structure of the journey between Chapters II and X of the Gita is again a structure to be ‘seen’ in order to be understood. It shares the same kind of ontological union – viewpoint dependence as the structure of crisis. Through the mediation of memory – the lived memories of Arjuna’s past, the imaginative variations of a life lived and forgotten – Arjuna is able in these chapters to refeel his body as it felt and thought in different contexts: samkhyayoga(II); karmayoga (III): the yoga of action; jnanayoga (IV): the yoga of knowledge; karmasamnyasayoga (V): the yoga of renunciation of actions; dhyanayoga (VI): the yoga of meditation; jnanavijnanayoga (VII): the yoga of wisdom and understanding; aksarabrahmayoga (VIII): the yoga of the imperishable Brahman; rajavidyarajaguhyayoga (IX): the yoga of sovereign knowledge and sovereign secret; and vibhutiyoga (X): the yoga of manifestations. Within each one of these contexts, world-body-feelings are different; the intentionality of the context determines actions and the way these actions world-body-feel. This long journey of lost memories is a journey of re-embodiment. It demands an ontological reduction grounded on the realization of the non-existence of any reference for language, perception or experience in general. But the conclusion of such a re-embodiment shows the futility of trying to grasp substances or anything permanent. Chapter XI of The Gita shows the fmality, dissolution and despair of any world grounded on permanence; yet it remains a world and a body alive (XI. 23-30).

Note: the greatest linguistic sin in The Gita is the ahamkara, literally the ‘I-maker’ (X. 42). The most favored modality of seeing oneself in the world is the anahamvadin, literally ‘not-I’ speaking (X-VIII. 19, 26, 40).

‘Aham‘ emphasizes the agent in an artificial way for the simple reason that the personal suffix to the verb alone suffices to specify the agent. The reason for the use of aham has been more concerned with the partial aspect of momentary interest, on the emphasis placed on individuation for the sake of clarification: aham yaje (It is I who sacrifices as opposed to yaje, I-sacrificing). Indian philosophy has made extensive use of what is Sanskrit is ahamkara, literally ‘the I-maker’. It is understood as a principle of artificial individuation of any and all particulars. However, by using aham the speaker would be committed to a way of speaking which would ‘create the impression that’ (or talk ‘as if’) the individual had an ultimate ontological identity with the activity-whole.

The Bhagavad Gita portrays three basic types of agency in Chapter XVIII, verses 19-40, which can be explained in terms of these modalities, ahamhkara and anahamvadin.

Instrumental agency is paradigmatic of the ‘agent’ of ‘light’ (sattvika) who allows the cosmic ritual of karman, samsara and dharma to play itself out or appear through the body (XVIII. 23). Here the ‘agent’ in the instrumental case is on a par with the body or material instrument through which an interpretation appears (III. 27); the efficient cause is not to be distinguished from the cause of the movement or interpretation made flesh through the material cause or body.

Dative agency is paradigmatic of the ‘agent’ or ‘passion’ (rajasa), who is accordingly disparaged in Indian culture, for he continues ignorantly to bind himself to the wheel of sathsdra and to accumulate karma-phala(fruits of action) (XVIII. 24).

Dative agency is also typical of the ‘agent’ of ignorance and darkness (tamasa), who is even worse off than the ‘agent’ or passion, for he acts blindly, with no knowledge of dharma or how things ‘hang together’ (XVIII. 25).

Thus, if the individual subject were to be understood as material instrument through which movement appeared, lie was expressed in the instrumental case. If he were to be understood as a partaker of the action and vitally interested in the outcome as to whether it might be of benefit or disadvantage to him, he was expressed in the dative case. The wise man would speak as anahamvadin (not-‘I’ speaking).

This is the end of Arjuna’s moves through the first 11 chapters of The Gita. What we see in this journey of Axjuna is that the memories he re-embodies are lived memories. Arjuna himself has gone through them and therefore knows how they world-body-feel. Arjuna is able to body-feel his own body while travelling the corridors of his memories. He is able to body-feel other body-feelings he himself was when those memories were not memories but a living body. He knows of other world-unions which are possible through himself or that he himself has been. But again, as phenomenology reminds us, these body-unions are problematic. One may decide to ascribe these memories, all these imaginative variations, to the same constant body, i.e. one may decide to ascribe them to a body which remains constant through all these variations and to whom memories (imaginative variations) are never recoverable as embodied, but are only possible as embodied attributes from a logical world to a logical subject. This union is a precarious one, a theoretic unity to which different sensations, different body-feelings, may be ascribed or may be denied. Man can never find himself at home in such a body, and the only way out for man is either to declare himself in crisis or diligently to dedicate himself to the task of finding his own emancipation.

The problem of reading

If we take language as a sign, and then read from Chapters II through XI of The Gita, our reading will of necessity be blind, like the King of the Kurus. Each chapter is a field, a yoga or dharma, and the entities within each chapter arise and collapse with each chapter.* No entity, theory or body carries over from chapter to chapter, even if the names do. Each field arises by cancelling the previous one and each self-body, Arjuna-Krsna prakrti-purusa, body-perspective arises anew within the boundaries of each chapter with which it shares its dimensions and demarcations. Furthermore, the movement of the fields cancels out the movement and continuity of any entity or substance. Time cannot be read as duration, nothing lasts; but as Chapter XI clearly states, time is the movement of one self-body perspective to another, the shift of the perspective of one field to the perspective of another field. And space cannot be read as distance, but as the rising or falling of two simultaneous perspectives, Arjuna’s-Krsna’s. Both these perspectives are complementary yet contradictory; what can truly be said in one cannot be truly said in the other. Finally, the duration of any one life or self-body lasts as long as a field and rises and dies with it. But the question remains: by which grammar are we going to read this text? Or, more precisely, by which conditioning model of language was the text composed?

*Thus the human body as base frames the imagination in the Bhagavad Gita as the experiences of ‘I’ and ‘not-I’: the Ahamkara and the Anahamvadin. In the structure of The Gita, these two experiences coincide with Chapters I and XI. Between these two experiences, the meditator’s body is systematically dismembered in a multiplication of bodies that coincide with each one of the yogas of each chapter between II and X. Once the meditator has become the frame of a whole background, as in Chapter XI, the focus of the imagination – what the meditator does after the great experience – is a systematic development of focusing with backgrounds only in mind, and this is the function of the chapters between XII and XVIII. This is known in The Gita as the movement of the gunas.

Thus the text of meditation is built like a musical composition and so are the criteria for reading it. It is built in four steps, like a tuning theory: an original blank string; the dismembered string in multiple divisions; the birth of new tones and their sacrifice for new ones to rise, and the identity of singer and song by sharing the same dimension. Audial cultures will vary in the order of procedure. Buddhism will begin and end with the absolute Zero: the absolute experience, ineffable and incommunicable. Hinduism will strive for the One. In either case the problem of reading them is not so different from one another for both ultimately agree that the language of cognition as grounded on the cognitive skills of epistemology, and the language of imagination as grounded on experience are complementary in the sense that what is true, or can truly be said in one, is not true and cannot truly be said in the other.

The text of meditation has certain decisive advantages. Instead of reducing all signs to a cognitive science like semiology it opens language to context and establishes the imagination as a source of languages and signs. It liberates language from the inhuman constraint of universality while giving it the public domain of its function. Above all it divorces the texts of cognition from those of the imagination by establishing different sets of rules of reference. Without the above provisions the passage from human sinner to human saint or much less the simple process of acquiring different organized levels of sensitization would not be possible.

The text of meditation needs to be explored further for it shows that an archeology of the imagination does not exhaust the text of the imagination; nor is the imagination exhausted by doing what we have done in this paper, namely to abstrast from it its languages and structures. These languages and structures become, for the text of meditation, memory-points to guide the imagination.

III. The model of both languages (the primacy of movement, detachment and embodiment)

Taking our clue from The Gita’s insistence that sensation is a language, we find ourselves forced to establish also that perspective is also sensation, or reality. Aduna’s body in Chapter I is both body-perspective, prakrti-purusa, Arjuna-Krsna, and so is his body in Chapter XI. But by then everything has changed. Faith (XII) is no longer any thing or any god, but a space beyond any god. Knowledge (XIII) is no longer the absolutized universal knowledge that led him into crisis, but rather: ‘Know me, O Bharata, to be the knower of the field in all the fields; the knowledge of the field and of the knower of the field: This I hold to be (real) knowledge (XIII. 2).’ And the body (XIV-XVIII) will emerge as a radical embodied unity, which appears as multiplicity of body-feelings-sensations, complete each time it acts, in every action, in every social situation. But to retrain the body to ‘think itself up’ every time it acts requires not only time but also the constant effort and habit of learning how to shift perspectives, progressing from the perspective of Chapter I to the perspective of Chapter XI.

This simply means that from now on we cannot read the Gita without simultaneously reading the movement of the three gunas and the simultaneity of both prakrti-purusa, Arjuna-Krsna.

The strangeness of the new situation demands a critical change not only in conceptual structures, but also a relearning of the new process of body-feelings, a re-education of the muscular and nervous systems, the opening of the frontal lobes and the heart, and above all a change in conceptual structure to account for the new situation. This is the change during which a whole new style of embodied interpretation is assembled, but this is not achieved without an intellectual bereavement which can only proceed to relearn its own process of formation step by step, action by action. It is for this reason that Chapters XIV to XVIII are fundamental to The Gita, for they are the chapters which show the ‘rehabilitation’ process of a man who has seen the emptiness behind his own old structure of meaning and does not yet know how to proceed in the integration of the new.

What Krsna proposes to Arjuna from the start of Chapter XIV is that for Arjuna, who has already seen, every action is ‘dangerous’, for each one contains the creation and dissolution of the world. The creation of the new world is accomplished if in every action Arjuna orients himself through the buddhi-interpretation of action. The world will destroy itself if in every action Arjuna orients himself through the interpretation of the manas. But this program of living is only for one who has ‘held to this wisdom (Krsna’s) and become the likeness of my own state of being’ (XIV. 2). For these are the people who ‘are not born even at creation, nor are they destroyed at dissolution’ (XIV. 2). They are humans who have learned to transcend the gunas of prakrti (XIV. 19-20).

From now on, Arjuna the warrior has to tread carefully, for every step is dangerous, every step in his world is explosive. In no way can Arjuna, the warrior, abandon himself in any action, not even those full of sattva (XIV. 6).

Arjuna, obviously is bewildered and lost while trying to give body-shape to his new vision (XIV. 21), but Krsna states simply the absolute criterion for knowledge, solely by realizing that it is only the gunas which act when we witness activity, by remaining as if unconcerned without attributing or appropriating pleasure or pain to oneself, that one may stand apart and remain firm, without doubt (XIV. 23-25).

Arjuna has to learn that in every action, every step he takes, the whole creation is present. It is the upturned peepal tree, with its branches below, its roots above. The branches stretch below and above, nourished by the gunas; its sprouts are the sense objects. When this tree reaches the world of men, it spreads out its roots that result in action (XV. 1-2). But men do not see how their actions are so umbilically joined to the whole world. They do not comprehend its form, nor its beginning, nor its foundation. Their only release is to cut this firmly rooted tree with the weapon of non-attachment (V. 3).

The patient waiting for the right conditions to see, or give embodied shape to the new vision which Arjuna has just touched in Chapter XI should be nothing new to Arjuna the warrior. Take a piece of land and there will be as many perspectives as men passing through it. But for a warrior every piece of land is all the life there is. The discipline of his own training as a warrior has, in many ways, prepared Arjuna already for detachment, and for the silent lust for life, and for each of the things of life. His disciplined training as a warrior has already prepared him to immerse himself in every action without fully surrendering to it. His ear is always cocked to anticipate any danger, even while immersed in every action. In fact, there is only every single action for him to count on as ‘his life’ as a warrior, and it is in every action that he will have to throw himself with the full power of his decisions.

Arjuna’s conclusion at the end of his long journey, in terms of a philosophy which would give shape to his vision of Chapter XI, is obviously a coincidence with Krsna: to realize his own emancipation through the action facing him by reading the conditioning of all life. Through that action Krsna, Arjuna, purusa, prakrti and their foundation coincide. For emancipation to be possible, however, Arjuna’s will (body-self) has to coincide with the original cultural will of which both Krsna and Arjuna are the bodies. But this realization could not have been mediated had Arjuna not been able to ‘body-think himself up’ (XVIII. 73) and share with its cultural orientation its dimensions and demarcations. A man of culture is a man with his feet always on the human flesh. The human flesh is the ultimate ground of all theory and no theory can substitute for that (as the ground) without amputating human life.

The model of language according to the criteria of sound – the truth is in the string

Taking our clue from Plato, we have, at this time, to end this the way he ends the Symposium, ‘by letting the band of musicians and clowns in and spoil the order of the banquet’. No Western philosopher since Plato has taken the model of music with its ‘aural’ directions and ‘context dependency’ as a model of rationality. This is precisely what we claim is the case if we are going to understand radically the basic orientation of The Gita.

It is obvious that The Bhagavad Gita is an aural/oral document from an aural/oral culture. We claim its model of language to be ruled by sound criteria. This is all we need to assume for what follows. These criteria are apriori for any knowledge of the Gita to be possible.

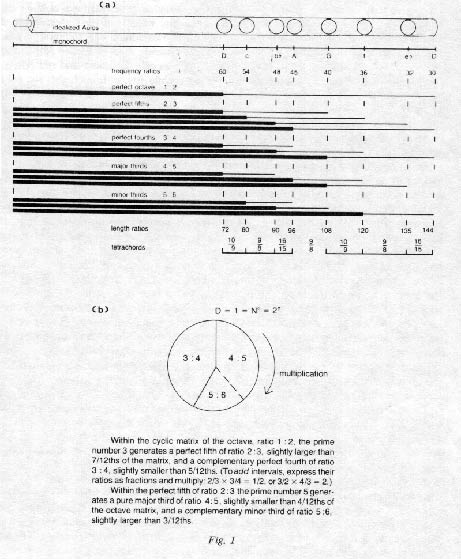

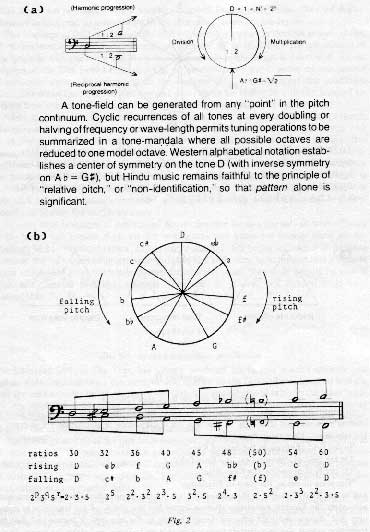

No later than the third millennium BC, and probably more than a thousand years earlier, man discovered that the intervals between the tones could be defined by the ratios of the lengths of pipes and strings which sounded them [Fig. l(a)]. It was the ear that made ratios invariant; by its vivid memory of the simpler intervals, the ear made the development of a science of pure relations possible within the theory of numbers, the tone-field being isomorphic with the number field. From this musicalized number theory, which we know as ‘ratio theory’, but which the ancients simply called ‘music’, man began his model building. The ratios of the first six integers defined the primary building blocks: the octave 1:2, the fifth 2:3, the fourth 3:4, the major third 4:5, and the minor third 5:6. From these first six intergers, functioning as multiples and sub-multiples of any reference unit (‘1’) of length or frequency, a numerological cosmology was developed throughout the Near and Far East [Fig. 1(b)]. The ultimate source of this ‘Pythagorean’ development is unknown. The hymns of the Rg Veda, The Gita, Buddhism, and so on, resound with the evidence that their authors were fully aware of or conditioned by this science and alive to the variety of models it could provide.

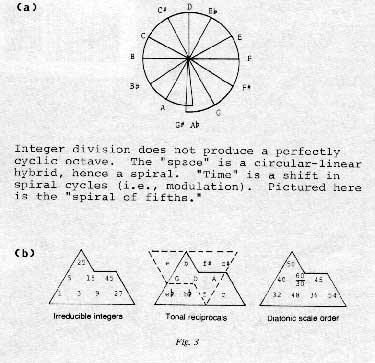

Tones recur cyclically at every doubling or halving of frequency or wavelength which are reciprocal: vrtra-agni; prakrti-purusa; Arjuna-Krsna; samsara-nirvana: thus the ‘basic miracle of music’ [Fig. 2(a)]. From this acoustical phenomenon, the number 2 acquires its ‘female’ status; it defines invariantly the octave matrix within which all tones come to birth [Fig. 2(b)]. Here, in this initial identification of the octave with the ratio 1:2, is the root of all the problems which haunt the acoustical theorist, problems which the ancient theorist conceived as symbolizing the imperfection and disorder of the universe, and also its renewal through new tones, new births, new songs, new gods. The octave refuses to be subdivided into subordinate cycles by the only language ancient man knew – the language of natural number, or integers, and the rational numbers derived from them [Fig. 3(a)]. It is a simple arithmetical fact that the higher powers of three and five which define subordinate intervals of music never agree with higher powers of two which define octave cycles [Fig. 3(b)]. It is a man’s yearning for this impossible agreement which introduced a hierarchy of values into the number field. For our ancestors, the essence of the world and of the numbers which interpreted that world was sound, not substance, and that world was rife with disagreement among an endless number of possible structures and possible worlds. The epistemological field of sound, however, remained invariant.

Therefore, from a linguistic and cultural perspective, we have to be aware that we are dealing with languages where tonal and arithmetic relations establish the epistemological invariances. Invariance was not physical, but epistemological. Ratio theory was a science of pure relations; its fixed elements came from the recognition of the octave, fifth and derivative tonal relations which made ratio concrete. The divorce of music from mathematics came later. Language grounded in music is grounded thereby on context dependency; any tone can have any possible relation to other tones, and the shift from one tone to another, which alone makes melody possible, is a shift in perspective which the musician himself embodies. Any perspective (tone) must be ‘sacrificed’ for a new one to come into being; the song is a radical activity which requires innovation while maintaining continuity, and the ‘world’ is the creation of the singer, who shares its dimensions with the song. The octave remained the epistemological invariant, ‘Mother-Earth’, of which all these worlds are the offspring.

Tuning theory establishes for us certain epistemological criteria which we need bear in mind if any meaning is to be derived from any culture which takes tone as the ground of language: (a) it is not the case that numbers or ratios control movement, but it is the case that movement may be ordered according to certain ratios; we are not watching the movement of certain sounds, but rather, we are watching how movement becomes certain sounds (the body is the carrier of particular backgrounds); (b) tones may be generated by numbers; this generation does not give us isolated elements, but rather constellations of elements in which each tone is context and structure dependent (the background is the primary focus); (c) within the matrix of the octave any tonal pattern may rise or fall, hence opposite or reciprocal possibilities are equally relevant, both in the sense of time (shift of key – modulation) and space (rising-falling) (the problem of choice, duality); (d) any perspective remains just one out of a group of equally valid perspectives, and the variety of possible perspectives from which to view any set of tones is apparently inexhaustible; any realization (that is, any song) excludes all other possibilities while it is sounding, but no song has so universal an appeal that it terminates the invention of new ones (the possibilities of dismemberment and the temporality of the body); (e) linguistic statements remain structure- and context-dependent, and the function of any language is to make clear its own dependence on, and reference to, other linguistic systems; a model based on the primacy of sound is not based on the reality of substance. Whereas the eye fastens on what is fixed, the ear is open to the world of movement in which ‘existence’ (sat) and ‘non-existence’ (asat), Arjuna-Krsna, prakrti-purusa are locked in an eternal and present absence/presence.

Music is a field of aural dimensions where the only substance is its own structure plus the dynamic movement which carves it out from the reverberant sphere of silent potentiality. There are no lasting invariants – the form of the construction and the ‘rules of the game’ last only as long as the duration of the piece. Each tone is subject to redefinition and shifts in perspective as soon as a piece is completed. Unlike an architectural (i.e. spatial) construction, which once completed remains static, its elements forever locked into a set pattern, a musical piece comes and goes. It is called and recalled into existence any number of times, during which it exists as concretely as any visual or tactile construction. Each time a piece is played, it is carved anew out of an infinite source of sound possibility, and each subsequent playing is an act of creation.

Each act of creating, though physically/aurally separate, is connected to each and every other act of creation by a continuous path of memory and movement, lending as much concreteness’ to a musical world as notions of metric distance lend to a visual/tactile world.

It is precisely its transience which gives a sound-universe its dimensions. By its continual motion and the possibility of superimposing perspectives, either literally or through memory, music functions within a field which transcends three-dimensional static space. Each note springs forth from a sort of infinite-dimensional musical manifold, an unbounded space of shifting tonal possibilities.

A form, or song, born of this space becomes one possibility manifest, one possibility existing at the temporary sacrifice of all other possibilities. A choice must be made for existence to be. A song can be sung in only one key at a time to be recognizable as a coherent form/song, and for this choice of key, tuning system, interpretation and the like to be made, is to sacrifice all other possibilities for the duration of the piece’s performance. But since a musical creation can be called and recalled into being any number of times, the ‘sacrifice’ is not a dogmatic invariant.

No choice, however, is an absolute in the field of time, for perspectives can change, either after a piece is completed or within its own structure, in the form of modulation to another gravitational center. But modulation is not a random jump. There is always the linking factor of memory. Modulation has no meaning without the memory of where the song came from and where it is going. Each movement is glued together by a memory which flows in a continuous omni directional path. Direction and intent in music are based on a memory of the immediately preceding events but also on an image of the construction in its entirety. It is this continuity of memory which determines the forward motion of the piece and the meaning of each tone when it is recalled in subsequent playing – the tones have no choice but to slide along the path already charted by memory.

Had we not removed music from the curriculum we might not have so much difficulty in understanding audw cultures, and therefore in recovering our own memories. For this reason, any one construction of these cultures is simultaneously a deconstruction. We are forced to cross a sound barrier which we did not know existed and which originally was taken for granted or was slowly being forgotten. Sound gave birth to symbol, but we cannot exalt the offspring without killing the mother. Thus, it is obvious that statements from audial cultures will remain unintelligible as long as they are not read against the background model which generates them: the model of music as model of language.

It should also be amply clear that it is only through such radical activity that our rationality can know itself as rational by embodying other people’s rationality, rather than colonizing them into our own decisions about rationality.

Conclusion

The first discovery we have made when approaching documents from audial cultures is that ‘the book’ as a model of reading is dead. That what lives is the text. (The book is dead, long live the text!) The book as the model of reading carries with it a host of presuppositions that belong exclusively to literary cultures: the unity of the text, the uniformity of language, the exclusive focusing on content, the fixity of both the reader and the text, the accidental changes in the reader of the text as attributes of a fixed subject, the exclusive function of language as sign, the identification of content with knowledge, the coincidence of knowledge with our model of reading, the ontological and axiological priority of purusa over prakrti, etc., etc.

On the other hand, a document from oral cultures appears simultaneously as an explosion of different texts, different languages and different functions of language in such a way that when taken together in any ‘one’ text from audial cultures they offer us a complete and wholly new communications-systems. To enter the system demands from us, interpreters or translators, the ability to discover the plurality of languages and texts, and also perform the kinds of activities that such discovery would entail so that we may write a text of the audial culture under study. The Gita for example gives us the language of prakrti, and the language of purusa and the common language of tuning theory and mathematics of which both languages emerge plus the relation of these languages to the body-in every case body and language coincide in dimensions – and simultaneously we are forced to develop a way of focusing in each one of these languages by the criteria and intentionality of the language and of the system as a whole. While in one language we may focus on substances and content, in the other we have to learn how to focus on fields and movement. The problem of the translator or the interpreter, therefore, is not so much to give us a consistent and uniform translation of the text, but rather to open the plurality of texts to the possibility that texts as much as languages and cultures are incommensurable. Incommensurable texts, or languages, are neither inconsistent with each other nor comparable for content. (We, of course, can make them, by a dictionary, inconsistent and their content comparable.) Unless we are capable of doing this we may miss the picture that emerges from reading a document like the Gita in its totality of text, plural languages and plural bodies where at times (prakrti) the body and the language coincide improperly and there is room for personal agency and where at times (purusa) the language and the body coincide to the point of sharing the same dimension and then there is no room for agency but only witnessing.

This essay would be incomplete if the implications of the method used here to analyze the text of The Gita were not generalized to apply to other disciplines. Literary criticism of modem as well as mythic materials has taken many forms and in every case each form has been identified with one particular kind of ‘knowledge’ to which the cultural text has been reduced. Few have taken the rationality of mythology seriously enough to realize that the models they carried to its study could in no way coincide with the source of the knowledge from which mythology was bom in the first place and which was no knowledge at all. literary criticism has not been very much aware of its own criteria of interpretation much less the criteria of constitution of others. The same criticism may be applied to philology that could only interpret The Gita if it were reduced to an epic document – and epic criteria – just because it is found in The Mahabharata. But what philogists, anthropologists etc. fail to realize is that what is at stake in the study of culture is not only their claims to knowledge but that the knowledge those disciplines carry with them to the study of culture cancels those cultures out, and that in this cancellation we systematically reduce the plurality of cultures to an imperialistic uniformity. And since language is sensation and vice versa, we are systematically cutting off possible sensitization mechanisms for contemporary culture.

For some, culture is a geographic concept; for others, something in the blood. But in the end for all of us our homeland is language, for only on its soil we can conceive and feel our own existence. Whichever decision we can make on method, it results in a language and therefore in a sensitization mechanism. The oral mechanisms of oral cultures focus on wave-functions which determine a biological type of human – our ancestor – different from the optical men of the visual world that transforms wave-functions to generate event4ype objects and the viewpoint that goes along with this world. If we study the past it is out of a biological necessity to resensitize ourselves to a world that is in eternal motion and depends for sensitization on our own ability to move conceptually first, biologically later. What India has discovered for us – Hinduism and Buddhism – is a language to describe consciousness as witness, the purusa of the Yoga-Sutra or the Krsna/purusa of The Gita, for example, and it also gave us a language, another different language to speak about objects and things, cabbages and kings: the language of prakrti. What we have lost in the West is not the ecstasy, the oceanic experience, but the language to describe such experiences. Thus we have misread the East in one of its most fundamental contributions: the experience of immortality in the form of the consciousness as witness in this very world and by the same yogin who now may be enlightened and now unenlightened, who now experiences Yoga or now talks or writes about Yoga. Because we lost the language, we lost the body that could intelligibly integrate experience and interpretation and we lost the community. We do not realize that the possibilities of the human body are in direct proportion to the languages it can embody. We opted for an interpretation that together with one language would also presuppose one body that is either enlightened or stupid and we decided never to mix the two. Classical Samkhya, Classical Yoga and The Gita, not to mention Buddhism, are the worst victims of our paucity of language, bodies, in a word, inner mobility.

Ultimately our emphasis has to be biological because primarily and ultimately, our right and wrong methods, our ethics and metaphysics are grounded on a biological origin and are capable of subverting our biology into a higher or lower degree of sensatization. The biological emphasis of the body in documents like the Gita is obvious, and also a result of the method here used, and it becomes even more obvious when the experiences of the I and the not-I – mortality and immortality – are both housed in the body, in the human biology and not away from it. The same happens with ethics. When we see two opposing armies being destroyed as in The Gita or two groups of people killing each other, historical adversaries, then we know a theory of knowledge is dying or living with those people; biological life dies or lives with the theories that sensitize it.

The ultimate concern for the method we propose is the fact that through it we expand the languages of the cultures surrounding us, rather than return to the mysterious, and that through these expansions we increase the sensitization mechanisms of the humanity with which we find ourselves in community.

Appendix I

|

|

|

Appendix II

Translation and the language of purusa

Taking our clue from the first verse of the Gita, ‘on the field of the Kurus, the field of dharma‘, we see that this early in the text the discrepancies in translation are as many as the translators. Here are some samples:

‘In the field of virtue, in the field of Kuru’

‘On the field of righteousness, the Kuru field’

‘On the field of justice, the Kuru-field’

‘The place of virtue, the place of Ngriinage’

and so on. What is missing in these translations is not the ‘happy phrase’ that would translate accurately the Sanskrit kuruksetre dharma-ksetre but the ability of the translator to recognize that dharma and field (dharma-ksetre) belong to the language of purusa and that the translator cannot give us a discrete term but must learn to focus, and make the reader do the same, in the total fields, wholes, contexts, horizons etc.

Chapter XIII of the Gita defines clearly the field as the ability to focus and become (Chapter XI) those fields.

Thus we have one language of fields totally different from the language of discrete objects.

While in one we may easily find a discrete equivalent English term, in the other the English terms are lacking; and so is the ability to focus on fields, contexts, wholes etc.

The language of fields and the ability to focus on them appears in the Cita in such wholes as: Krsna/purusa/yoga/dharma/ksetre/gunas‘ Chapter XI of the Gita is the coincidence of this language with the body and the oceanic experience of the world in front of it. All the chapters of the Gita from I through XVIII are an exercise (Yoga) in seeing the dependence of particular words and statements on the concrete field, whole, context that conditions them. The emancipation of Arjuna consists primarily in his ability to shift the focus of his actions from the actions to the field, context, dharma, yoga, guna that conditions it.

While the language of prakrti demands, for the sake of identification, the fixity of things, situations and subjects, the language of purusa brings forth the correction of this fixity with its ability to focus on movement, offering as criteria for such movement an embodied vision, that is a-perspectival, detached and without any room for self-identity. Self identity gives way to witnessing. Any forms of identification of such experiences with any subject are possible only when the language of purusa is cancelled, and the language of prakrti is the only language to describe experience. And vice versa the language of purusa describes only such states of ‘oceanic experience’ and to give it priority over the language of prakrti would also destroy the worlds we know.

In sum, both languages of prakrti and purusa describe for us a plurality of ways of being in the world not because these are the worlds oral men knew but because these are the languages he had to describe them. As you may notice the Gita begins and ends with Samjaya choosing the only form of narration available to him and telling us in the end that whenever Krsna and Arjuna meet the whole human drama starts again. This could equally be said of texts like Classical Samkhya, Classical Yoga and, in general, any classical texts from oral cultures.

Appendix III

The text of the imagination: meditation

The Bhagavad Gita, as The Text, has already produced for us two texts: a semiotic text and an audial/musical text. The semiotic text is alien to the Gita and we identified it as the text the reader carries to the reading of the Gita. The audial/musical text, on the other hand, we have identified as the model text by which the Gita, so to speak, wrote itself. Our present study would be incomplete if we stopped here. We need to proceed farther, one text farther, to prove the necessity under which we are laboring.

The language models of the two texts mentioned above differ radically from each other as to their origins. The semiotic text is grounded on principles (of abstraction). The audial/ musical text is grounded on origins (of experience). The semiotic text is an exclusive product of abstraction through cognitive skills. The audial/musical text is an abstraction from the imagination and imaginative skills.

The third text, the text of meditation, is an exclusive product of the imagination. But before we proceed any farther we should distinguish the use of the imagination by the Gita from the way the imagination has been described by others. Freud buried it in the subconscious while lung confused it with fantasy and falsely identified its origin with Greek archetypes. (When, in his later writings, Jung focused of Eastern archetypes he was closer to the imagination than to fantasy.) The main distinction we have to bear in mind between imagination and fantasy, is that fantasy’s origins, development and conclusion rise and fall with its creator; they live and die within the covers of a book, a text or a story. The imagination’s origins, on the other hand, are public and universal and the creations of the imagination transcend any individual texts and affect always the world: they create new worlds. Fantasy may give rise to feelings, in most cases sentiment or sentimentality, but the imagination leads always to decisions that change, affect or somehow create new worlds. The imaginations’ feelings are of a different kind and intensity than those of fantasy and they require an external and experienced guide for decoding or interpreting them.

The Bhagavad Gita, as a text for meditation, shares with the imagination its limits and demarcations. The main elements of the text are memory and imagination. Imagination functions as origin, the original experience of which a whole religion, a whole culture, is born: the original archetype. Memory, on the other hand, provides the imagination with image-points – memory-points – of concrete instances, manifestations of that imagination – that silent background – made flesh.

The meditator’s task is a movement through memory-points to steal the imagination’s horizon: to become the experience, to make his body coincide with the limits and demarcations of that horizon.

The method of the imagination in meditation is an exclusive concentration, a dedicated focusing on only those signs that come from the background. In the case of the Gita it is a play of discernment of the inner sign of detachment between the disciple, Arjuna and his guru Krshna.

The text of meditation in the Bhagavad Gita may be better understood if moved in its entirety to the human body as its base: the body, its operations and its possible embodiments. The human body of the meditator comes to the meditation in an apparent false unity of experience that the meditation is going to dismember systematically in order finally to steal the larger unit of the horizon. (Re-read footnote on pp. 276-277.)

Antonio T. de Nicolas was educated in Spain, India and the United States, and received his Ph.D. in philosophy at Fordham University in New York. He is Professor Emeritus of philosophy at the State University of New York at Stony Brook.

Dr. de Nicolas is the author of some twenty- seven books, including Avatara: The Humanization of Philosophy through the Bhagavad Gita,a classic in the field of Indic studies; and Habits of Mind, a criticism of higher education, whose framework has recently been adopted as the educational system for the new Russia. He is also known for his acclaimed translations of the poetry of the Nobel Prize-winning author,Juan Ramon Jimenez, and of the mystical writings of St. Ignatius de Loyola and St. John of the Cross.

A philosopher by profession, Dr. de Nicolas confesses that his most abiding philosophical concern is the act of imagining, which he has pursued in his studies of the Spanish mystics, Eastern classical texts, and most recently, in his own poetry.

His books of poetry: Remembering the God to Come, The Sea Tug Elegies, Of Angels and Women, Mostly, and Moksha Smith: Agni’s Warrior-Sage. An Epic of the Immortal Fire, have received wide acclaim. Critical reviewers of these works have offered the following insights:

from, Choice: “…these poems could not have been produced by a mainstream American. They are illuminated from within by a gift, a skill, a mission…unlike the critico-prosaic American norm…”

from The Baltimore Sun: “Steeped as they are in mythology and philosophy these are not easy poems. Nor is de Nicolas an easy poet. He confronts us with the necessity to remake our lives…his poems …show us that we are not bound by rules. Nor are we bound by mysteries. We are bound by love. And therefore, we are boundless”

from William Packard, editor of the New York Quarterly: ” This is the kind of poetry that Plato was describing in his dialogues, and the kind of poetry that Nietzsche was calling for in Zarathustra.”

Professor de Nicolas is presently a Director of the Biocultural Research Institute, located in Florida.